Transactions¶

Introduction¶

Transactions are essential components of blockchain networks, enabling state changes and the execution of key operations. In the Polkadot SDK, transactions, often called extrinsics, come in multiple forms, including signed, unsigned, and inherent transactions.

This guide walks you through the different transaction types and how they're formatted, validated, and processed within the Polkadot ecosystem. You'll also learn how to customize transaction formats and construct transactions for FRAME-based runtimes, ensuring a complete understanding of how transactions are built and executed in Polkadot SDK-based chains.

What Is a Transaction?¶

In the Polkadot SDK, transactions represent operations that modify the chain's state, bundled into blocks for execution. The term extrinsic is often used to refer to any data that originates outside the runtime and is included in the chain. While other blockchain systems typically refer to these operations as "transactions," the Polkadot SDK adopts the broader term "extrinsic" to capture the wide variety of data types that can be added to a block.

There are three primary types of transactions (extrinsics) in the Polkadot SDK:

- Signed transactions: Signed by the submitting account, often carrying transaction fees.

- Unsigned transactions: Submitted without a signature, often requiring custom validation logic.

- Inherent transactions: Typically inserted directly into blocks by block authoring nodes, without gossiping between peers.

Each type serves a distinct purpose, and understanding when and how to use each is key to efficiently working with the Polkadot SDK.

Signed Transactions¶

Signed transactions require an account's signature and typically involve submitting a request to execute a runtime call. The signature serves as a form of cryptographic proof that the sender has authorized the action, using their private key. These transactions often involve a transaction fee to cover the cost of execution and incentivize block producers.

Signed transactions are the most common type of transaction and are integral to user-driven actions, such as token transfers. For instance, when you transfer tokens from one account to another, the sending account must sign the transaction to authorize the operation.

For example, the pallet_balances::Call::transfer_allow_death extrinsic in the Balances pallet allows you to transfer tokens. Since your account initiates this transaction, your account key is used to sign it. You'll also be responsible for paying the associated transaction fee, with the option to include an additional tip to incentivize faster inclusion in the block.

Unsigned Transactions¶

Unsigned transactions do not require a signature or account-specific data from the sender. Unlike signed transactions, they do not come with any form of economic deterrent, such as fees, which makes them susceptible to spam or replay attacks. Custom validation logic must be implemented to mitigate these risks and ensure these transactions are secure.

Unsigned transactions typically involve scenarios where including a fee or signature is unnecessary or counterproductive. However, due to the absence of fees, they require careful validation to protect the network. For example, pallet_im_online::Call::heartbeat extrinsic allows validators to send a heartbeat signal, indicating they are active. Since only validators can make this call, the logic embedded in the transaction ensures that the sender is a validator, making the need for a signature or fee redundant.

Unsigned transactions are more resource-intensive than signed ones because custom validation is required, but they play a crucial role in certain operational scenarios, especially when regular user accounts aren't involved.

Inherent Transactions¶

Inherent transactions are a specialized type of unsigned transaction that is used primarily for block authoring. Unlike signed or other unsigned transactions, inherent transactions are added directly by block producers and are not broadcasted to the network or stored in the transaction queue. They don't require signatures or the usual validation steps and are generally used to insert system-critical data directly into blocks.

A key example of an inherent transaction is inserting a timestamp into each block. The pallet_timestamp::Call::now extrinsic allows block authors to include the current time in the block they are producing. Since the block producer adds this information, there is no need for transaction validation, like signature verification. The validation in this case is done indirectly by the validators, who check whether the timestamp is within an acceptable range before finalizing the block.

Another example is the paras_inherent::Call::enter extrinsic, which enables parachain collator nodes to send validation data to the relay chain. This inherent transaction ensures that the necessary parachain data is included in each block without the overhead of gossiped transactions.

Inherent transactions serve a critical role in block authoring by allowing important operational data to be added directly to the chain without needing the validation processes required for standard transactions.

Transaction Formats¶

Understanding the structure of signed and unsigned transactions is crucial for developers building on Polkadot SDK-based chains. Whether you're optimizing transaction processing, customizing formats, or interacting with the transaction pool, knowing the format of extrinsics, Polkadot's term for transactions, is essential.

Types of Transaction Formats¶

In Polkadot SDK-based chains, extrinsics can fall into three main categories:

- Unchecked extrinsics: Typically used for signed transactions that require validation. They contain a signature and additional data, such as a nonce and information for fee calculation. Unchecked extrinsics are named as such because they require validation checks before being accepted into the transaction pool.

- Checked extrinsics: Typically used for inherent extrinsics (unsigned transactions); these don't require signature verification. Instead, they carry information such as where the extrinsic originates and any additional data required for the block authoring process.

- Opaque extrinsics: Used when the format of an extrinsic is not yet fully committed or finalized. They are still decodable, but their structure can be flexible depending on the context.

Signed Transaction Data Structure¶

A signed transaction typically includes the following components:

- Signature: Verifies the authenticity of the transaction sender.

- Call: The actual function or method call the transaction is requesting (for example, transferring funds).

- Nonce: Tracks the number of prior transactions sent from the account, helping to prevent replay attacks.

- Tip: An optional incentive to prioritize the transaction in block inclusion.

- Additional data: Includes details such as spec version, block hash, and genesis hash to ensure the transaction is valid within the correct runtime and chain context.

Here's a simplified breakdown of how signed transactions are typically constructed in a Polkadot SDK runtime:

Each part of the signed transaction has a purpose, ensuring the transaction's authenticity and context within the blockchain.

Signed Extensions¶

Polkadot SDK also provides the concept of signed extensions, which allow developers to extend extrinsics with additional data or validation logic before they are included in a block. The SignedExtension set helps enforce custom rules or protections, such as ensuring the transaction's validity or calculating priority.

The transaction queue regularly calls signed extensions to verify a transaction's validity before placing it in the ready queue. This safeguard ensures transactions won't fail in a block. Signed extensions are commonly used to enforce validation logic and protect the transaction pool from spam and replay attacks.

In FRAME, a signed extension can hold any of the following types by default:

AccountId: To encode the sender's identity.Call: To encode the pallet call to be dispatched. This data is used to calculate transaction fees.AdditionalSigned: To handle any additional data to go into the signed payload allowing you to attach any custom logic prior to dispatching a transaction.Pre: To encode the information that can be passed from before a call is dispatched to after it gets dispatched.

Signed extensions can enforce checks like:

CheckSpecVersion: Ensures the transaction is compatible with the runtime's current version.CheckWeight: Calculates the weight (or computational cost) of the transaction, ensuring the block doesn't exceed the maximum allowed weight.

These extensions are critical in the transaction lifecycle, ensuring that only valid and prioritized transactions are processed.

Transaction Construction¶

Building transactions in the Polkadot SDK involves constructing a payload that can be verified, signed, and submitted for inclusion in a block. Each runtime in the Polkadot SDK has its own rules for validating and executing transactions, but there are common patterns for constructing a signed transaction.

Construct a Signed Transaction¶

A signed transaction in the Polkadot SDK includes various pieces of data to ensure security, prevent replay attacks, and prioritize processing. Here's an overview of how to construct one:

-

Construct the unsigned payload: Gather the necessary information for the call, including:

- Pallet index: Identifies the pallet where the runtime function resides.

- Function index: Specifies the particular function to call in the pallet.

- Parameters: Any additional arguments required by the function call.

-

Create a signing payload: Once the unsigned payload is ready, additional data must be included:

- Transaction nonce: Unique identifier to prevent replay attacks.

- Era information: Defines how long the transaction is valid before it's dropped from the pool.

- Block hash: Ensures the transaction doesn't execute on the wrong chain or fork.

-

Sign the payload: Using the sender's private key, sign the payload to ensure that the transaction can only be executed by the account holder.

- Serialize the signed payload: Once signed, the transaction must be serialized into a binary format, ensuring the data is compact and easy to transmit over the network.

- Submit the serialized transaction: Finally, submit the serialized transaction to the network, where it will enter the transaction pool and wait for processing by an authoring node.

The following is an example of how a signed transaction might look:

node_runtime::UncheckedExtrinsic::new_signed(

function.clone(), // some call

sp_runtime::AccountId32::from(sender.public()).into(), // some sending account

node_runtime::Signature::Sr25519(signature.clone()), // the account's signature

extra.clone(), // the signed extensions

)

Transaction Encoding¶

Before a transaction is sent to the network, it is serialized and encoded using a structured encoding process that ensures consistency and prevents tampering:

[1]: Compact encoded length in bytes of the entire transaction.[2]: A u8 containing 1 byte to indicate whether the transaction is signed or unsigned (1 bit) and the encoded transaction version ID (7 bits).[3]: If signed, this field contains an account ID, an SR25519 signature, and some extra data.[4]: Encoded call data, including pallet and function indices and any required arguments.

This encoded format ensures consistency and efficiency in processing transactions across the network. By adhering to this format, applications can construct valid transactions and pass them to the network for execution.

To learn more about how compact encoding works using SCALE, see the SCALE Codec README on GitHub.

Customize Transaction Construction¶

Although the basic steps for constructing transactions are consistent across Polkadot SDK-based chains, developers can customize transaction formats and validation rules. For example:

- Custom pallets: You can define new pallets with custom function calls, each with its own parameters and validation logic.

- Signed extensions: Developers can implement custom extensions that modify how transactions are prioritized, validated, or included in blocks.

By leveraging Polkadot SDK's modular design, developers can create highly specialized transaction logic tailored to their chain's needs.

Lifecycle of a Transaction¶

In the Polkadot SDK, transactions are often referred to as extrinsics because the data in transactions originates outside of the runtime. These transactions contain data that initiates changes to the chain state. The most common type of extrinsic is a signed transaction, which is cryptographically verified and typically incurs a fee. This section focuses on how signed transactions are processed, validated, and ultimately included in a block.

Define Transaction Properties¶

The Polkadot SDK runtime defines key transaction properties, such as:

- Transaction validity: Ensures the transaction meets all runtime requirements.

- Signed or unsigned: Identifies whether a transaction needs to be signed by an account.

- State changes: Determines how the transaction modifies the state of the chain.

Pallets, which compose the runtime's logic, define the specific transactions that your chain supports. When a user submits a transaction, such as a token transfer, it becomes a signed transaction, verified by the user's account signature. If the account has enough funds to cover fees, the transaction is executed, and the chain's state is updated accordingly.

Process on a Block Authoring Node¶

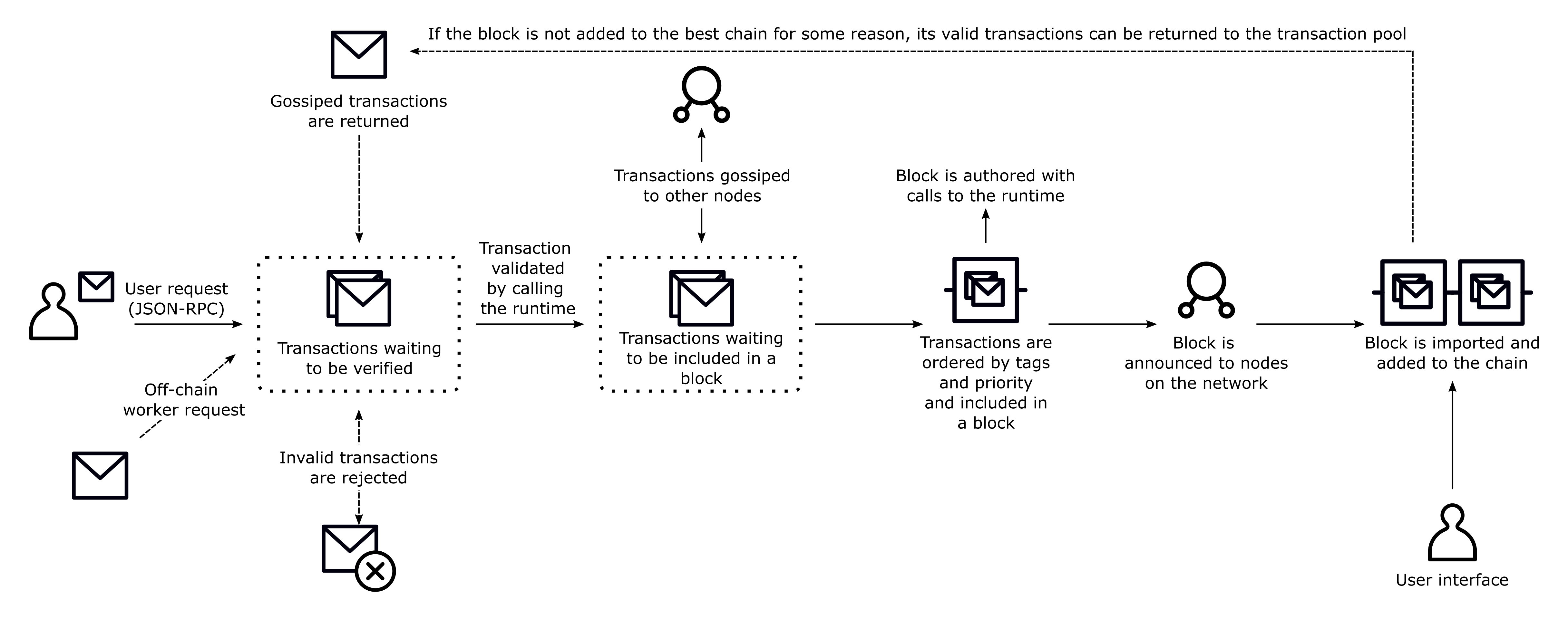

In Polkadot SDK-based networks, some nodes are authorized to author blocks. These nodes validate and process transactions. When a transaction is sent to a node that can produce blocks, it undergoes a lifecycle that involves several stages, including validation and execution. Non-authoring nodes gossip the transaction across the network until an authoring node receives it. The following diagram illustrates the lifecycle of a transaction that's submitted to a network and processed by an authoring node.

Validate and Queue¶

Once a transaction reaches an authoring node, it undergoes an initial validation process to ensure it meets specific conditions defined in the runtime. This validation includes checks for:

- Correct nonce: Ensures the transaction is sequentially valid for the account.

- Sufficient funds: Confirms the account can cover any associated transaction fees.

- Signature validity: Verifies that the sender's signature matches the transaction data.

After these checks, valid transactions are placed in the transaction pool, where they are queued for inclusion in a block. The transaction pool regularly re-validates queued transactions to ensure they remain valid before being processed. To reach consensus, two-thirds of the nodes must agree on the order of the transactions executed and the resulting state change. Transactions are validated and queued on the local node in a transaction pool to prepare for consensus.

Transaction Pool¶

The transaction pool is responsible for managing valid transactions. It ensures that only transactions that pass initial validity checks are queued. Transactions that fail validation, expire, or become invalid for other reasons are removed from the pool.

The transaction pool organizes transactions into two queues:

- Ready queue: Transactions that are valid and ready to be included in a block.

- Future queue: Transactions that are not yet valid but could be in the future, such as transactions with a nonce too high for the current state.

Details on how the transaction pool validates transactions, including fee and signature handling, can be found in the validate_transaction method.

Invalid Transactions¶

If a transaction is invalid, for example, due to an invalid signature or insufficient funds, it is rejected and won't be added to the block. Invalid transactions might be rejected for reasons such as:

- The transaction has already been included in a block.

- The transaction's signature does not match the sender.

- The transaction is too large to fit in the current block.

Transaction Ordering and Priority¶

When a node is selected as the next block author, it prioritizes transactions based on weight, length, and tip amount. The goal is to fill the block with high-priority transactions without exceeding its maximum size or computational limits. Transactions are ordered as follows:

- Inherents first: Inherent transactions, such as block timestamp updates, are always placed first.

- Nonce-based ordering: Transactions from the same account are ordered by their nonce.

- Fee-based ordering: Among transactions with the same nonce or priority level, those with higher fees are prioritized.

Transaction Execution¶

Once a block author selects transactions from the pool, the transactions are executed in priority order. As each transaction is processed, the state changes are written directly to the chain's storage. It's important to note that these changes are not cached, meaning a failed transaction won't revert earlier state changes, which could leave the block in an inconsistent state.

Events are also written to storage. Runtime logic should not emit an event before performing the associated actions. If the associated transaction fails after the event was emitted, the event will not revert.

Transaction Mortality¶

Transactions in the network can be configured as either mortal (with expiration) or immortal (without expiration). Every transaction payload contains a block checkpoint (reference block number and hash) and an era/validity period that determines how many blocks after the checkpoint the transaction remains valid.

When a transaction is submitted, the network validates it against these parameters. If the transaction is not included in a block within the specified validity window, it is automatically removed from the transaction queue.

-

Mortal transactions: Have a finite lifespan and will expire after a specified number of blocks. For example, a transaction with a block checkpoint of 1000 and a validity period of 64 blocks will be valid from blocks 1000 to 1064.

-

Immortal transactions: Never expire and remain valid indefinitely. To create an immortal transaction, set the block checkpoint to 0 (genesis block), use the genesis hash as a reference, and set the validity period to 0.

However, immortal transactions pose significant security risks through replay attacks. If an account is reaped (balance drops to zero, account removed) and later re-funded, malicious actors can replay old immortal transactions.

The blockchain maintains only a limited number of prior block hashes for reference validation, called BlockHashCount. If your validity period exceeds BlockHashCount, the effective validity period becomes the minimum of your specified period and the block hash count.

Unique Identifiers for Extrinsics¶

Transaction hashes are not unique identifiers in Polkadot SDK-based chains.

Key differences from traditional blockchains:

- Transaction hashes serve only as fingerprints of transaction information.

- Multiple valid transactions can share the same hash.

- Hash uniqueness assumptions lead to serious issues.

For example, when an account is reaped (removed due to insufficient balance) and later recreated, it resets to nonce 0, allowing identical transactions to be valid at different points:

| Block | Extrinsic Index | Hash | Origin | Nonce | Call | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 0 | 0x01 | Account A | 0 | Transfer 5 DOT to B | Account A reaped |

| 150 | 5 | 0x02 | Account B | 4 | Transfer 7 DOT to A | Account A created (nonce = 0) |

| 200 | 2 | 0x01 | Account A | 0 | Transfer 5 DOT to B | Successful transaction |

Notice that blocks 100 and 200 contain transactions with identical hashes (0x01) but are completely different, valid operations occurring at different times.

Additional complexity comes from Polkadot SDK's origin abstraction. Origins can represent collectives, governance bodies, or other non-account entities that don't maintain nonces like regular accounts and might dispatch identical calls multiple times with the same hash values. Each execution occurs in different chain states with different results.

The correct way to uniquely identify an extrinsic on a Polkadot SDK-based chain is to use the block ID (height or hash) and the extrinsic index. Since the Polkadot SDK defines blocks as headers plus ordered arrays of extrinsics, the index position within a canonical block provides guaranteed uniqueness.

Additional Resources¶

For a video overview of the lifecycle of transactions and the types of transactions that exist, see the Transaction lifecycle seminar from Parity Tech.

| Created: October 16, 2024